Use good tools and don’t overdo it

Ask a farmer, “When should I prune my apple trees?” and you will most likely hear, “March.” That’s an old tradition, but not because it is the only time to prune. You can prune any time. But March is a month on a farm when not so much is happening outdoors and farmers have time to prune their apples. Me? I often prune in the fall, or later in the spring when the ground dries out and it warms up. I say, “Prune when you have the time and inclination.”

Pruning serves a number of functions. First, for many of us, it helps to create a work of living sculpture. Next, pruning opens up a tree and lets sunshine hit every leaf so that it can produce food for the roots and fruits. A well-pruned tree will be healthier and produce tastier fruit. My pruning mentor told me decades ago that a bird should be able to fly through a well-pruned apple tree without getting hurt.

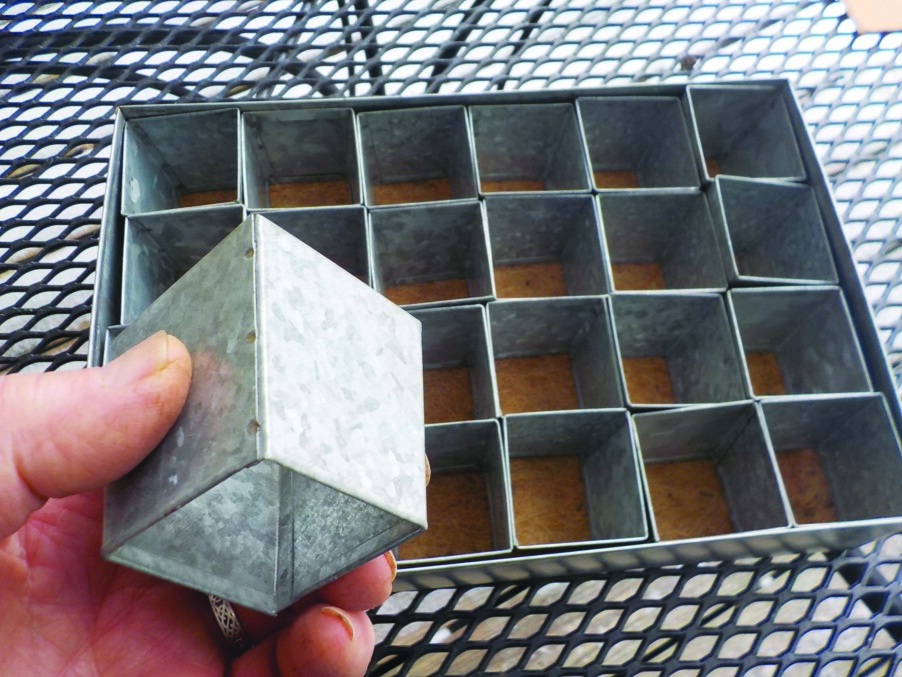

When pruning a fruit tree it’s important to know which branches will be blossoming and producing fruit. Look for fruit spurs on apples and pears. These are roughly 3- to 6-inch-long protuberances with buds on them. As you prune you will have to make choices about which of two branches to cut. Look for those fruit spurs, and be guided by them.

In general when making cuts on an older, neglected tree, it’s better to remove a few larger branches than to make many smaller cuts.

It’s important to know where to make your cuts. If you cut off a branch flush with the trunk you will create a bigger wound than if you cut it off a little farther out from the trunk. Notice that most branches swell a bit at their base. That swollen, wrinkled area is called the branch collar, and it is where healing takes place. Cut just beyond the collar. But if you cut too far out on the branch, you leave a stub which will not heal quickly — it will have to rot back to the collar before it can scab over.

Start by removing any dead or damaged branches. Cut them back to the trunk, or to a larger branch where they originate. Heavy wet snow and high winds this winter have created lots of broken branches. Clean them up. Knowing if a small branch is alive is easy: scrape it with your thumbnail. If it shows green, it is alive. Bigger dead branches will have flaky, discolored bark and will not be flexible if bent.

Remove any branches that are rubbing other branches. Keep the best-looking branch and remove the other. Remove any branch that is headed into the center of the tree instead of growing toward the outside.

Or perhaps you’d like to begin with the easiest branches to remove, the water sprouts. These are vertical shoots coming up from a more-or-less horizontal branch. They are very numerous in some trees, not so much in others.

Water sprouts are generally a tree’s response to a need for more food for the roots. Trees that haven’t been pruned in years have many of these as there are many leaves shaded out and not producing much food for the roots. Or after a heavy pruning, a tree may produce lots of water sprouts to replace food-producing branches that have been removed.

If water sprouts are not removed when they are the thickness of a pencil or a hot dog, they will become as thick as your arm or leg and be difficult to remove. Clean those up every year.

You can change the angle of growth of a branch that is only an inch or less thick. Once winter is over, attach string or rope to a branch and tie it to a peg in the ground or to a weight to bend it down. A half-gallon milk jug works well. Just add water until you have the correct angle on the branch. Forty-five to 60 degrees off vertical is fine. You can remove the weights in June. Branches that are 45 degrees from the horizontal produce more fruit than more vertical branches.

If you have to remove a bigger branch, do it in two steps. First make a cut 2 or 3 feet out from the trunk to reduce the weight of the branch. Then make a second cut just outside the branch collar. Use one hand on the saw, one hand supporting the weight of the branch. That will prevent tearing the bark on the trunk if it falls before you finish the cut.

When pruning, don’t overdo it. Trees need their leaves to feed the roots and fruit. In any given year don’t take more than 25 percent of the leaves (woody stems don’t count when calculating how much you have taken off). In winter you just have to estimate how much live wood you can take off.

A few words on tools: The basics are a good pair of hand pruners, kept sharp. A good pair of geared loppers for medium-sized branches. A good hand saw with a tri-cut blade for branches bigger than an inch or so. Don’t buy the cheapest you can find. Buy the most expensive you can afford. My new curved Stihl hand saw went through a 3-inch apple branch like a hot knife through butter. With the leather sheath, it cost about $65 and is worth every penny.

Featured photo: Fruit spur on an apple tree will produce fruit and leaves. Photo by Henry Homeyer.