A look at a new roller risk and advice on picking your perfect skates

A New spin

Remix Roller Rink offer all-ages fun

By: Michael Witthaus

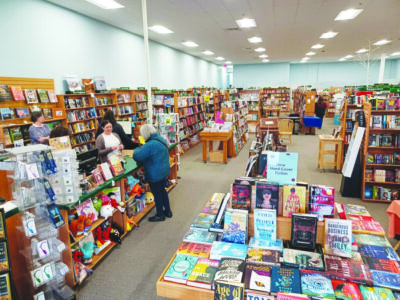

With the opening of Remix Skate and Event Center in December, New Hampshire now has a commercial roller rink, its first since 2019, when Great View Rollerskating in Enfield closed. The new business, however, isn’t a throwback, even if their logo’s stripey lettering evokes the ’70s roller disco craze. Rather, it’s a modern take on the concept, aimed at multiple demographics.

Along with a capacious hardwood rink, Remix offers several swankier touches, like upscale pub food, craft beer and a machine that makes design-etched cotton candy. Children’s birthday parties are a staple, but Remix also hosts things geared to an older crowd, like an 18+ R&B Night held Jan. 6, and similar ’90s and Latin events.

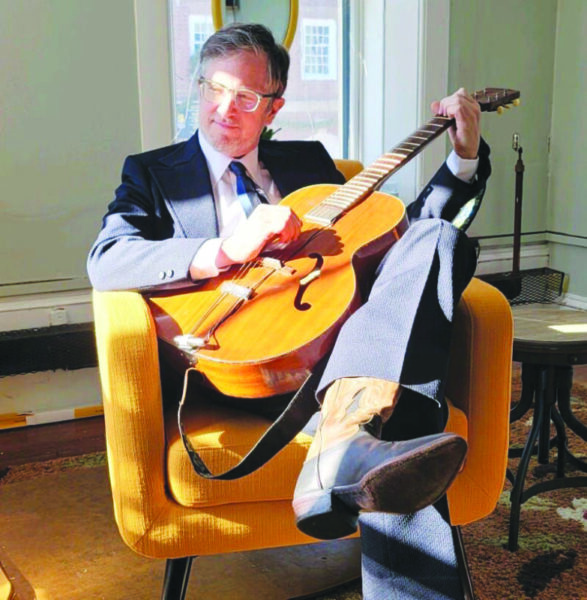

Matt and Kelly Pearson were rollerbladers in high school but haven’t skated much since. They’re also entrepreneurs, who tend to start businesses that align with their lives at a given moment. Before they met, Matt was a wedding DJ. After marriage and kids, they opened Cowabunga’s Indoor Kids Play & Party Center on Huse Road in Manchester.

Their oldest child, a son, is now 16 and has outgrown jungle gyms. Rather than buy him a minibike or snowmobile, the Pearsons began eyeing the now-vacant space next to Cowabunga’s and thinking about a solution for other teenagers like theirs. They considered opening a bowling alley, which didn’t particularly excite them, then thought about expanding the indoor playground, but soon the two began conceiving Remix.

“That kind of vibe is ingrained in me. There’s no better place for a hang than a roller-skating rink,” Matt Pearson said. “There’s not really any places for teens to hang out … so we were like, alright, if we make a roller rink, what would that look like in 2023? Would it be neon floors and birthday parties … a roller-skating rink of the ’80s and ’90s? No, it would be what those kids would want in modern times.”

Finding a way to make it work was the first and biggest challenge, beginning with the size. Matt called the Huse Road location “a little bit of a boutique venue.” Poles and an odd floor layout meant the skating area would only be around two-thirds the size of a regulation rink. The Pearsons turned this liability to their advantage.

“We learned through Covid that we can capacity control,” Matt said. “With back-end ticketing, we have limits. The rink was smaller than others we were accustomed to, but at the same time, we don’t have to pack it with that many people. That’s how you find a sweet spot of capacity, seating space and other amenities to make the whole thing jive.”

On the other hand, the idea of hosting roller derby matches had to be scrapped. “We worked with the New Hampshire Roller Derby Girls, had them in early to take a look at the space, to see if an opportunity was there,” Matt said. “They said, ‘it’s great and we love it … for dinner and drinks, but we can only use this maybe for practice.”

A few of the Derby Girls, however, work at Remix as servers and rink hosts. “It’s a relationship that’s worked out pretty well,” he said, adding, “one thing we learned is we weren’t necessarily bringing roller skating back to New Hampshire, because there is an underground scene with a lot of skaters.”

Remix has enough space for live music, when the time comes.

“Roller rinks of old just needed a DJ booth, but we’re trying to remix this idea, so we made the stage a little bit bigger,” Matt said. “Maybe an ’80s cover band that we love will come over and do a night with us, with pro skaters…. It’s an amazing opportunity for really fun nights.”

For now, skaters can reserve two-hour slots Tuesday through Sunday, with either classic quad skates or rollerblades included in the $20 cost. Skaters can switch from one to the other midway as well. Initially, more patrons are opting for old-style wheels.

“Blades are the minority,” Matt said, “but for my generation, I think we’re a rollerblade crew.”

The Pearsons are pleased to offer wholesome fun for all ages.

“It’s still a family entertainment venue,” Matt said. “All the little characteristics that we brought to Cowabunga’s, we’re bringing here. There’s no better place to do a birthday party than a roller rink, and we can execute that on the weekends. But the after-work scene, 18-plus and 21-plus nights out, is the unspoken opportunity.”

Deciding what to call this new place turned out to be the easiest piece of the endeavor.

“It’s really a remixed version of roller skating in modern times,” Matt Pearson said. “What better name to call it than Remix?”

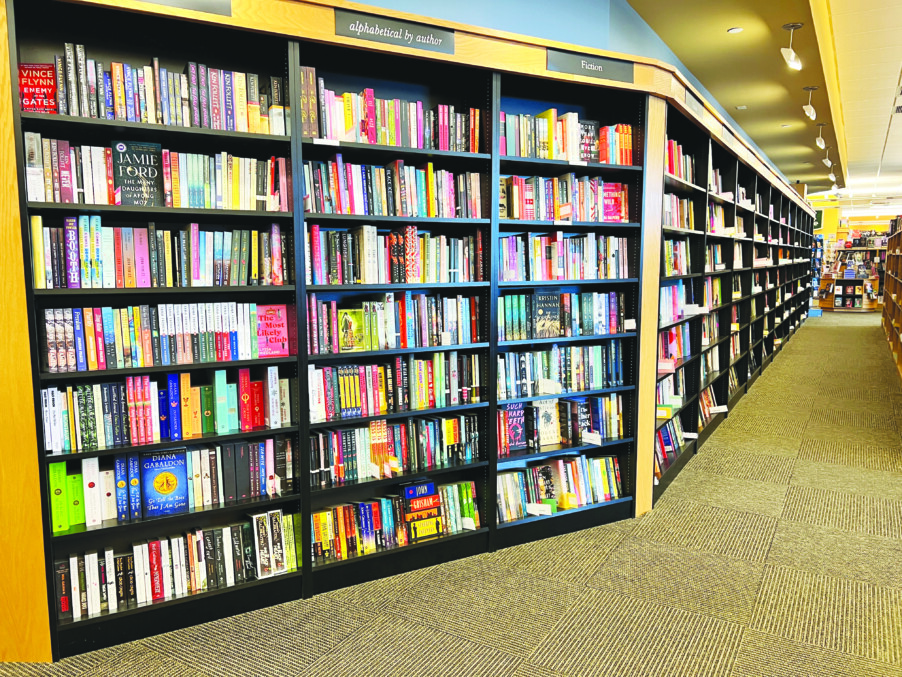

Find your skates

Expert help for picking your new set of wheels

By: Angie Sykeny

Eric Jones, manager at Bruised Boutique Skate Shop in Nashua, discussed the essential considerations and tips for new and experienced roller skaters, emphasizing the importance of proper fit, safety gear and skating etiquette.

What should beginners consider when choosing roller skates?

Beginners should prioritize finding skates that best fit their foot shape. Budget is an important consideration, but the trickier aspect is ensuring a good fit. Since people’s feet come in various shapes, it’s recommended to visit a store, like us — we’re the only one in New England, though — to try on different skates. This approach helps in finding a pair that is best suited to the individual’s foot shape, whether they are kids or adults.

How do you determine the right size?

In a store, it’s a matter of guess and check to find the right fit. Online it’s more challenging, and exchanges might be necessary if the fit isn’t right. However, most introductory-level skates are designed to accommodate a wide variety of foot shapes, making it less likely to get the wrong fit. … For adults, most roller skate brands size their skates close to men’s shoe sizes as a standard. Generally, using your men’s shoe size should give you a relatively safe fit. For women, that’s typically about one-and-a-half sizes down from their shoe size. Children’s roller skates are made in kid sizes, which should match their shoe size. Sizes range from Junior 10 through 13 and then size 1 and 2. It’s advisable to consider room for growth, so kids often leave with a size larger than their measured size.

What safety gear is necessary for skating at a roller rink?

At roller rinks in our area, safety gear is optional, so you don’t necessarily need anything. However, for kids it’s common to use knee pads, elbow pads, wrist guards and sometimes helmets, especially if they’re going to be skating outdoors. Combo packs that include knees, elbows and wrists are available and affordably priced for kids. For adults, they usually opt for knee pads and wrist guards, skipping elbow pads. Wrist guards are particularly smart to have since falls can impact the wrists. While safety gear is not strictly necessary for rinks, it is recommended for activities like roller derby, skating in skate parks, and outdoor skating, where helmets are advised.

What types of helmets are available for skating?

The helmets available for skating are mostly derived from skateboarding styles. There are basic helmets designed to be cushy and cost-effective for general use. For those engaged in more practical purposes like skating outdoors or activities like roller derby, certified helmets are available. These certified helmets have the same safety certifications as bike helmets and are made of a hard foam that can crack under a significant impact to provide better protection.

What additional protective gear would you recommend for people who are prone to accidents?

Besides the standard ensemble of knee pads, elbow pads, wrist guards and helmets, we also recommend padded shorts, often referred to as butt pads. These padded shorts are especially useful for those engaged in roller derby, skatepark activities and outdoor skating. They provide extra protection for falls and are a good option for anyone who feels they might be prone to falling a lot at the rink, especially for adults who are just learning to skate.

What tips would you give to first-time skaters for a safe and enjoyable experience?

Go slow and wear safety gear while learning. It’s also important to be aware of the unwritten rule at roller rinks: fast skaters should stay on the outside, while slower skaters should stay closer to the middle. This helps maintain safety and order in the rink.