Help your plants make it through winter

If you are like me, you buy new perennials, trees and shrubs every year. Most plants sold locally are hardy, but not all. It’s good to know the “zone hardiness” of plants before you buy them, and how the zone maps work. In a nutshell, the colder the climatic zone, the lower the number.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has created maps showing the climatic zones of all states and regions. They are based on many years of temperature records, and rate each zone according to the coldest average temperatures in each zone. Summer temperatures are not considered in creating the hardiness zones.

Each zone covers a 10-degree range of temperatures. The coldest zone in New England is Zone 3, which includes places where temperatures each winter range between minus 40 and minus 30 degrees Fahrenheit. Some maps include an “a” and “b” designation to further describe the zones. An “a” is 5 degrees colder than a “b.” So Zone 4a is minus 25 to minus 30, and 4b is minus 20 to minus 25.

Trees and perennial plants that survive in Zone 4, which includes much of Maine, Vermont and New Hampshire, should be hardy to minus 30 degrees, though we often only see minus 20 degrees. Zone 5 is minus 20 to minus 10, Zone 6 covers areas where temperatures range between minus 10 and zero, and Zone 7, which includes much of Rhode Island, temperatures only drop down to zero or 10 degrees above.

All that said, you can grow perennials, trees and shrubs that are not rated to be hardy in your zone. The key is to get them well-established before winter arrives and to provide them with growing conditions that are optimal: sun, soil and moisture levels that correspond to their needs. You probably cannot grow perennials and woodies that are rated for two zones warmer than yours, but one zone is generally possible.

Some trees and shrubs will survive in a colder zone but might not bloom every year. Or ever, for that matter. Here in Zone 4, old-fashioned wisteria vines that do well in Connecticut or Rhode Island will survive but their flower buds (which are set the summer before) are spoiled by our cold, so they do not bloom.

Harvey Buchite of Rice Creek Gardens in Blaine, Minnesota, wanted a wisteria that would bloom in his Zone 4 gardens. He was given a seedling on his wedding day 34 years ago, one started from a seed of a fairly tough hybrid. His turned out to be a wonder vine, and he named it the Blue Moon Wisteria and sold it for many years. It blooms reliably after winter temperatures of 30 below. The reason for its success? Blue Moon, unlike most other wisteria, blooms on shoots grown in the current season — on new wood.

I called Harvey Buchite in 2006 and he reported that even after hard winters it will bloom, and often three times each summer. I’ve had one since 2004 and get a very nice set of blooms each year around the Fourth of July. It usually re-blooms a little in the fall. Others have been developed since then that will bloom in Zone 4, including “Amethyst Falls,” which I grow and like even better.

Survival rates in a cold winter can be improved by mulching the roots of your delicate or borderline-hardy plants. I bought a Japanese andromeda this year, even though it is only hardy to Zone 5. In the fall I spread a thick layer of leaves around the base to keep the roots warm as winter approached. I could have used bark chips instead, which is also a good mulch.

Trees and shrubs extend their roots in the fall up until the ground freezes, and I wanted my little shrub to grow as big a root system as possible. And later, when temperatures drop to minus 20 and below, I wanted to keep the roots protected.

That andromeda was loaded with flower buds when I bought it. I may wrap it with burlap or landscape fabric to protect those blossoms from harsh winter winds, though I haven’t yet. In the long run it will have to survive on its own — I have too many plants to fuss over them all every year. The first year is always the most important — once established, plants are tougher.

Sometimes freezing and thawing of the ground will push a plant up and part way out of the soil. This allows roots to be exposed to the air, freezing and dehydrating. That is almost always lethal. But this usually only happens the first winter after planting. Check new plants after a thaw, and if a plant has popped up, push it back down and mulch it well.

Wrapping shrubs or small trees with burlap or a synthetic, breathable cloth will help to protect flower buds from desiccation and dieback. I find roses in my climate often are badly burned by winter winds, but I rarely do anything to protect them. I just cut back the roses to green wood in April or May, and they bloom nicely. I cut back a nice double red “Knockout” rose to the ground this past spring, and it rewarded me with dozens of blossoms all summer, starting in June.

I do lose some plants to winter conditions most years, but don’t feel bad about that. As I see it, I learn something each time one dies, and losing one plant means I can try a new one! Or, if a particularly loved plant does not survive in one location, I may buy another and plant in a different spot.

Henry’s book, Organic Gardening (not just) in the Northeast: A Hands-On, Month-by-Month Guide has been re-printed and will be shipped to people who ordered it soon.

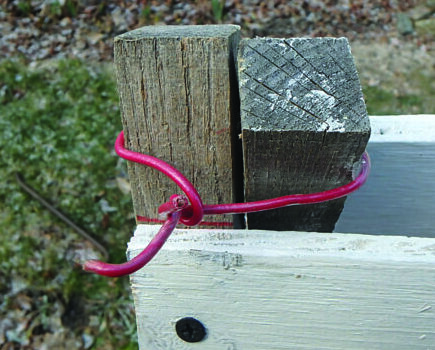

Featured Photo: Blue Moon wisteria blooms on new wood, so is not bothered by cold winters. Photo by Henry Homeyer.