The latest from NH’s theater, arts and literary communities

• ArtWeek continues: City Arts Nashua’s virtual ArtWeek is going on now through Sunday, Oct. 24, highlighting local artists and their works through professionally filmed segments, aired each day on Access Nashua Community Television (Comcast Channel 96) and the City Arts Nashua website (accessnashua.org/stream.php) and posts on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and LinkedIn. Coinciding with KidsWeek Nashua, ArtWeek also features a kids scavenger hunt with 50 mini art kits, filled with supplies for painting, sewing and sculpture projects, hidden around Nashua’s public sculptures. See the full story at hippopress.com; you’ll find it in the Oct. 14 issue. Or visit cityartsnashua.org for social media links.

• The art of carpet: A new special exhibition, “As Precious as Gold, Carpets from the Islamic World,” opens at the Currier Museum of Art(150 Ash St., Manchester) on Saturday, Oct. 23. It features 32 carpets with various geographical origins, dating from the 15th century to the 19th century, including a Spanish rug, three Egyptian rugs, Lotto and Holbein patterned carpets, a 16th-century Ushak Medallion and a late 17th-century Small Medallion carpet. The exhibit, on loan from the Saint Louis Art Museum, will be at the Currier until Feb. 27, 2022. Museum admission costs $15 for adults, $13 for seniors age 65 and up, $10 for students, $5 for youth ages 13 through 17, and is free for members and children under age 13. Museum hours are Thursday from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., and Friday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Call 669-6144 or visit currier.org.

• ’90s on stage: It’s the final week for The Seacoast Repertory Theatre’s (125 Bow St., Portsmouth) production of Cruel Intentions: The ’90s Musical. Based on the 1999 teen movie, the musical follows Sebastian and Kathryn, a pair of manipulative step-siblings who place a bet on whether or not Sebastian can seduce the school headmaster’s daughter Annette, who had published an essay advocating for abstinence until marriage. Showtimes are Thursday, Oct. 21, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, Oct. 22, at 8 p.m., and Saturday, Oct. 23, at 2 and 8 p.m. Ticket costs range from $32 to $46. The show will also be available to watch livestreamed on Friday and Saturday, with tickets priced at $25 for one viewer, $40 for two viewers and $60 for three or more viewers. Visit seacoastrep.org or call 433-4472.

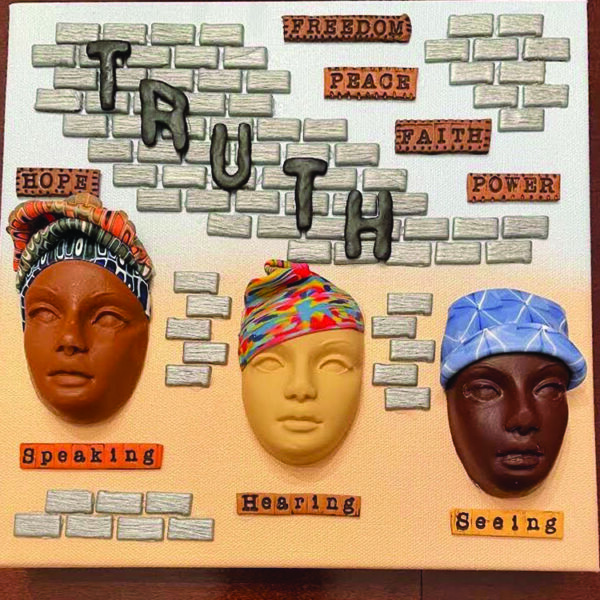

• Women explore race: Two Villages Art Society presents a new exhibit, “Truth Be Told: An Artful Gathering of Women,” at the Bates Building (846 Main St., Contoocook) from Oct. 23 through Nov. 13. The exhibit is a collaboration of 14 women artists — seven who identify as Black and seven who identify as white — from across the country who have been meeting bi-weekly over Zoom to discuss race. “This is a unique group of outstanding artists who share a fervent desire to understand and eradicate racial injustice in our country and are motivated to pursue this goal through their art,” Alyssa McKeon, president of Two Villages Art Society, said in a press release. Gallery hours are Wednesday through Friday, from 1 to 5 p.m., and Saturday and Sunday, from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. An opening reception with two of the artists will be held on Saturday, Oct. 23, from noon to 5 p.m. Visit twovillagesart.org.

• A musical message: The Portsmouth Symphony Orchestra will perform its fall concert at The Music Hall Historic Theater (28 Chestnut St., Portsmouth) on Sunday, Oct. 24, at 3 p.m. The concert will feature Tchaikovsky’s Tempest, Julius Eastman’s “Gay Guerilla” and Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Together these pieces create “a complex musical metaphor of weathering and coming out of a storm; … a powerful message of the invincible human spirit; and a moving transition from darkness to light,” according to the orchestra website. Tickets cost $25 to $35 for adults, $25 to $30 for seniors age 60 and up and $20 for students. Visit themusichall.org or call 436-2400.

Lively art

The New Hampshire Art Association has two shows showcasing work by NHAA artists at Creative Framing Solutions (89 Hanover St., Manchester) through October. “The Joy of Life” features oil paintings on canvas by Sally Newman. The paintings depict cityscapes, still life and landscapes with bold and saturated colors that highlight the vitality of life. “I am excited to show people my paintings as they will get a different perspective of day-to-day living as I imagine it,” Newman said in a press release. “A Little of This, A Little of That” features photography by Jean Chase Farnum. Taken mostly in New England, the photographs capture scenes of daily life in different kinds of light. “I have come to appreciate all aspects of natural light that is available on a 24 hours basis from the sun, moon and stars,” Farnum said in the release. “Witnessing fundamental nature and nature’s simplicity within the world around me forms the basis for the presentation of my work.” Gallery hours are Tuesday through Friday, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Saturday, from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Call 320-5988 or visit nhartassociation.org.

ART

Exhibits

• “KICK-START!” Also known as “the shoe show,” this themed art exhibition from the Women’s Caucus for Art’s New Hampshire Chapter opens at Twiggs Gallery, 254 King St., Boscawen. The exhibit runs through Oct. 31. The shoe theme is expressed in a wide variety of works that include paintings, sculptures, artist books, drawings and mixed media pieces. Gallery hours are Thursday and Friday, from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., and Saturday, from noon to 4 p.m. Visit twiggsgallery.wordpress.com.

• JOAN L. DUNFEY EXHIBITION Features artwork in a variety of media by regional NHAA members and non-members that follows the theme “Portals.” On display at the New Hampshire Art Association’s Robert Lincoln Levy Gallery, 136 State St., Portsmouth. Now through Nov. 28. Visit nhartassociation.org or call 431-4230.

• “AROUND NEW HAMPSHIRE” On exhibit at the Greater Concord Chamber of Commerce’s Visitor Center, 49 S. Main St., Concord, on view now through Dec. 16. Featuring the work of New Hampshire Art Association member Elaine Farmer, the exhibit features her oil paintings embodying New Hampshire’s iconic views and ideals, ranging from mountain lakes and birch tree woods to historic landmarks. Visit concordnhchamber.com or nhartassociation.org.

• “AS PRECIOUS AS GOLD: CARPETS FROM THE ISLAMIC WORLD” Exhibit features 32 carpets dating from the 15th century to the 19th century. The Currier Museum of Art (150 Ash St., Manchester). Opens Oct. 23. Museum admission tickets cost $15, $13 for seniors age 65 and up, and must be booked online. Call 669-6144 or visit currier.org.

• “TRUTH BE TOLD: AN ARTFUL GATHERING OF WOMEN” Two Villages Art Society presents a collaborative exhibit of works by 14 women artists — seven who identify as Black and seven who identify as white — from across the country who have been meeting bi-weekly over Zoom to discuss race. On view Oct. 23 through Nov. 13. Bates Building (846 Main St., Contoocook). Gallery hours are Wednesday through Friday, from 1 to 5 p.m., and Saturday and Sunday, from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. An opening reception with two of the artists will be held on Saturday, Oct. 23, from noon to 5 p.m. Visit twovillagesart.org.

• “1,000 CRANES FOR NASHUA” Featuring more than 1,000 origami paper cranes created by hundreds of Nashua-area kids, adults and families since April. On display now at The Atrium at St. Joseph Hospital, 172 Kinsley St., Nashua. Visit nashuasculpturesymposium.org.

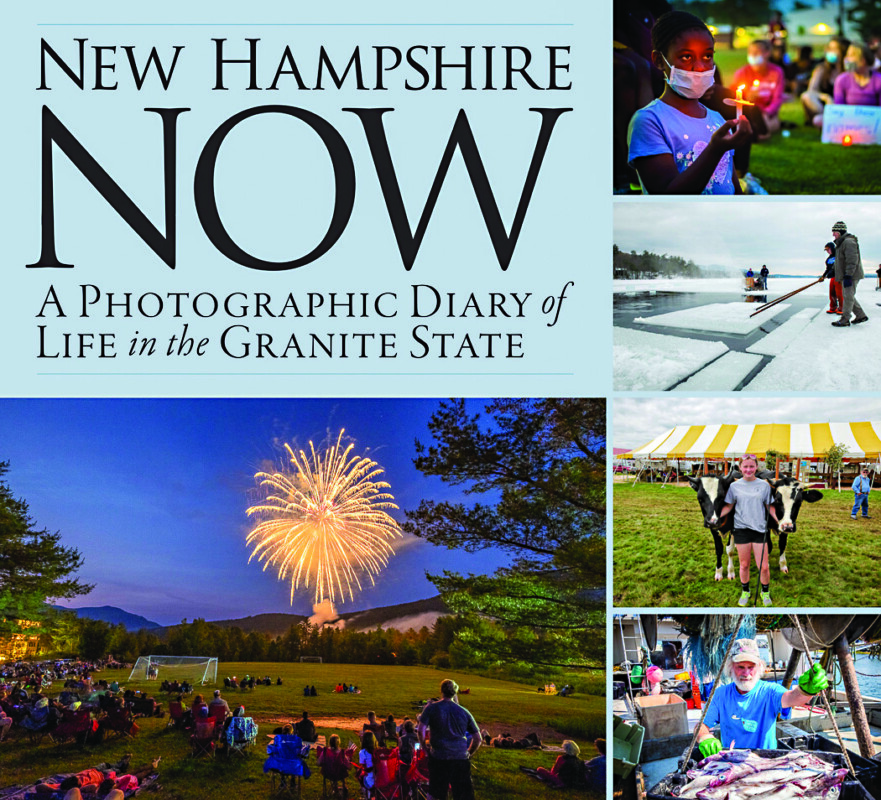

• “NEW HAMPSHIRE NOW” A collaborative photography project presented by the New Hampshire Historical Society and the New Hampshire Society of Photographic Artists, on display in eight exhibitions at museums and historical societies across the state. Nearly 50 photographers participated in the project, taking more than 5,000 photos of New Hampshire people, places, culture and events from 2018 to 2020 to create a 21st-century portrait of life in the Granite State. Exhibition locations are Belknap Mill in Laconia; Colby-Sawyer College in New London; Portsmouth Historical Society; Historical Society of Cheshire County in Keene; the Manchester Historic Association; Museum of the White Mountains at Plymouth State University; and the Tillotson Center in Colebrook; with the flagship exhibition at the New Hampshire Historical Society in Concord. Visit newhampshirenow.org and nhhistory.org.

• GALLERY ART A new collection of art by more than 20 area artists on display now in-person and online. Creative Ventures Gallery (411 Nashua St., Milford). Call 672-2500 or visit creativeventuresfineart.com.

• “TOMIE DEPAOLA AT THE CURRIER” Exhibition celebrates the illustrator’s life and legacy through a collection of his original drawings. On view now. Currier Museum of Art, 150 Ash St., Manchester. Museum admission tickets cost $15, $13 for seniors age 65 and up, and must be booked online. Call 669-6144 or visit currier.org.

• ART ON MAIN The City of Concord and the Greater Concord Chamber of Commerce present a year-round outdoor public art exhibit in Concord’s downtown featuring works by professional sculptors. All sculptures will be for sale. Visit concordnhchamber.com, call 224-2508 or email tsink@concordnhchamber.com.

THEATER

Shows

• CRUEL INTENTIONS THE ’90s MUSICAL The Seacoast Repertory Theatre (125 Bow St., Portsmouth) presents. Now through Oct. 23, with showtimes on Thursday at 7:30 p.m., Friday at 8 p.m., Saturday at 2 and 8 p.m., and Sunday at 2 and 7:30 p.m. Tickets cost $32 to $50. Visit seacoastrep.org.

• SPONGEBOB THE MUSICAL The Manchester Community Theatre Players present. In-person performance at MCTP Theatre at The North End Montessori School (698 Beech St., Manchester), and live streamed performance. Now through Oct. 23, with showtimes on Friday and Saturday at 7:30 p.m. Tickets cost $20 per person for the in-person show and $20 per streaming device for the live streamed show. In-person attendees must purchase tickets in advance and show proof of Covid-19 vaccination. Visit mctp.info or call 327-6777.

• AMERICAN SON The Hatbox Theatre (Steeplegate Mall, 270 Loudon Road, Concord). Now through Oct. 24, with showtimes on Friday and Saturday at 7:30 p.m., and Sunday at 2 p.m. Tickets cost $22 for adults, $19 for students, seniors and members and $16 for senior members. Visit hatboxnh.com.

• MAMMA MIA The Palace Theatre presents. 80 Hanover St., Manchester. Now through Nov. 14, with showtimes on Thursday and Friday at 7:30 p.m., Saturday at 2 and 7:30 p.m., and Sunday at noon and 5 p.m. Tickets cost $39 to $46 for adults and $25 for children. Visit palacetheatre.org or call 668-5588.

• HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Presented by Cue Zero Theatre Company. Oct. 22 through Oct. 24. Derry Opera House, 29 W. Broadway, Derry. Visit cztheatre.com.

• WONDERS Phylloxera Productions presents. The Hatbox Theatre (Steeplegate Mall, 270 Loudon Road, Concord). Oct. 29 through Nov. 7, with showtimes on Friday and Saturday at 7:30 p.m., and Sunday at 2 p.m. Tickets cost $22 for adults, $19 for students, seniors and members and $16 for senior members. Visit hatboxnh.com.

Classical

• “SUITES AND SCHUBERT” Symphony New Hampshire presents music by Bach, Schubert and Florence Price, the first African American female composer to have her music performed by a major symphony orchestra in 1933. Notable pieces will include Price’s Suite of Dances, Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 3, “Air on a G String,” and Schubert’s Symphony No. 5. St. Mary and Archangel Michael Coptic Orthodox Church (39 Chandler St., Nashua). Fri., Nov. 5. Visit symphonynh.org.