Back in the 1980s the Dartmouth Film Department showed a film by Les Blank called Garlic Is as Good as Ten Mothers. It was shown in “Smell-o-Rama.” Cooking garlic smells were mysteriously introduced to the air system, filling the 900-seat auditorium with the delicious odor of roasted garlic. I attended, and loved it all. Just for the record, my one mother was better than garlic — but I love garlic, too, and plant plenty of it.

One of my favorite fall appetizers is to take whole heads of garlic and roast them in oven-safe ramekins or small dishes at 375 degrees for 45 minutes or so. I peel off the outer layers of the head of garlic, cut off the tips of the head and drizzle it with olive oil. When done the cloves of garlic are soft and easily squeezed out of their skins after cooling. I like to serve this on crackers or a baguette spread with goat cheese.

In order to have enough garlic for treats like the one described above I plant a lot of garlic each October. Usually I plant about 50 cloves, but I have planted up to 100 — always enough to eat daily and some to share. It really is a virtually work-free, pest-free crop. All you need is “seed” garlic sold for planting, or failing that, some organic garlic purchased at your local farmers market or food coop. Grocery store garlic is often treated with chemicals so it won’t sprout.

In addition to seed garlic you need a sunny place with decent soil, or even crummy soil you can improve with compost. To plant 50 cloves of garlic the space you need is minimal: a spot perhaps 4 feet long and about 3 feet wide. You could even find the space in a flower bed for a few, or on the front lawn around the light pole.

I plant garlic in a wide raised bed. I loosen the soil with a garden fork or my CobraHead weeder down to a depth of 6 inches. Then I add some good-quality compost, either homemade or purchased, and stir it in. I make furrows 8 inches apart and add some organic fertilizer like Pro-Gro into the furrow. I work it in with my single-tined CobraHead weeder. Or you can sneak cloves into a flower bed individually using a hand trowel.

Each clove needs to be planted the way it grew — the fat part down, the pointy end up. I plant cloves about 3 inches deep and a hand’s width apart in the row. After pushing the clove into the loose soil I pat it down and when all are planted I cover the bed with about a foot of loose hay or straw. This will keep the garlic warm longer in the fall, allowing it to establish a good root system before the ground freezes.

Next spring the shoots will push right through the hay, but most weeds will not. If we have a warm fall, you might even see green shoots pushing through the hay now. Don’t worry. That won’t be a problem, come spring.

There are two kinds of garlic; hard-neck and soft-neck. Here in New England we do best growing hard-neck garlic. It has a stiff stem in the middle of each head where the scape grew last summer, while soft neck garlic does not.

Just as there are sweet onions and pungent onions that make you cry when you chop them, not all garlic tastes the same. If you are ordering garlic from a seed company, read the descriptions carefully. Be sure you are ordering hard-neck garlic. They should tell you about the flavor of each, and I recommend getting three different kinds for your first trial. Since seed garlic is relatively expensive, you will want to save some garlic each year for planting the next year.

If you use a lot of garlic in your recipes, pay attention to how many cloves are in each head. It is less work to peel one big clove than three small ones. I grow mainly large heads, and I often have to cut one clove into two or three pieces to fit it into my garlic press. The product description should tell you not only the size of the bulb but also the number of cloves per head.

You can store garlic best in a cool, dry place. Ideally 50 degrees with moderate humidity. You can freeze it in a zipper bag or jar for a year or more. Don’t store garlic at room temperature in oil, as it can produce deadly botulism.

Garlic plants are handsome, especially in July, when they send up tall flower scapes that twist and turn in great shapes. Think creatively and you can find a space to plant some. I often cut the scapes and use them in flower arrangements, and they are also good sliced and sautéed in a stir-fry.

In a recent article about putting the garden to bed, I failed to mention that it is a good plan to leave some flowers standing. Why? Because some beneficial insects lay eggs in or on the stalks to overwinter. Birds will also eat the seeds of things like black-eyed susans and coneflowers. So you have an excuse now not to clean up the gardens completely. You can finish in the spring.

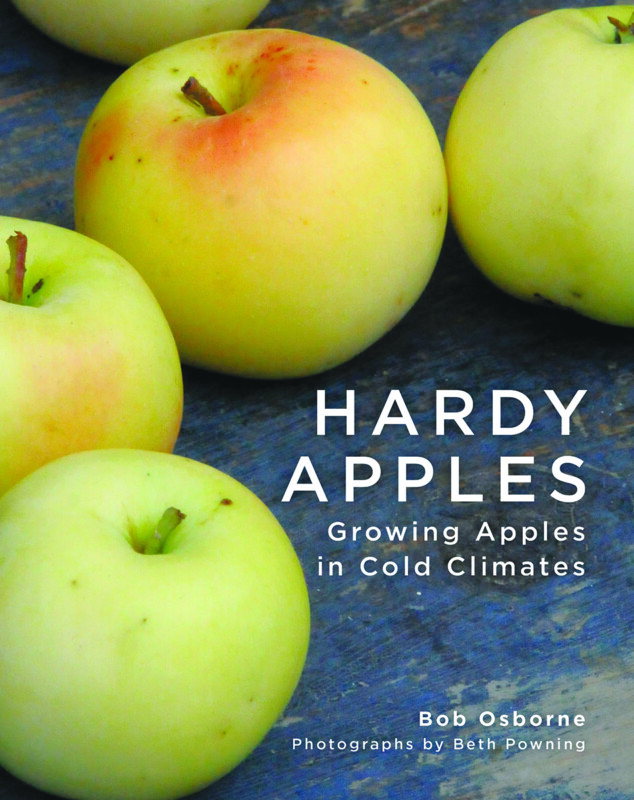

A garlic bed ready for planting. Photo by Henry Homeyer.