Gifts for the gardener

Ready to shop! Every time I turn on the radio or open a newspaper, there are articles about supply chain issues. Even the reliable old U.S. Postal Service is saying deliveries may well be delayed. So share some garden produce this year or shop at a local, family-owned business when you can.

Food is a great gift. You don’t need fancy fruit shipped from Oregon if you made plenty of tomato sauce or quince jelly this year. Share the harvest. A quart of dried cherry tomatoes contains a lot of love and work. You had to grow, harvest, wash and dehydrate. Only people dear to my heart will rate such a gift.

My dream gift? A friend, loved one or reader sending me a nice card, along with a homemade certificate for four hours of weeding in my garden. Or two hours. Working in the garden with a friend or relative can be a great way to strengthen a friendship. Politics don’t matter in the garden. I might suspect my brother-in-law didn’t vote the way I did in the last election. But if he will bring his chainsaw and help me take down and cut up a 12-inch-diameter box elder I want removed, send me the gift certificate!

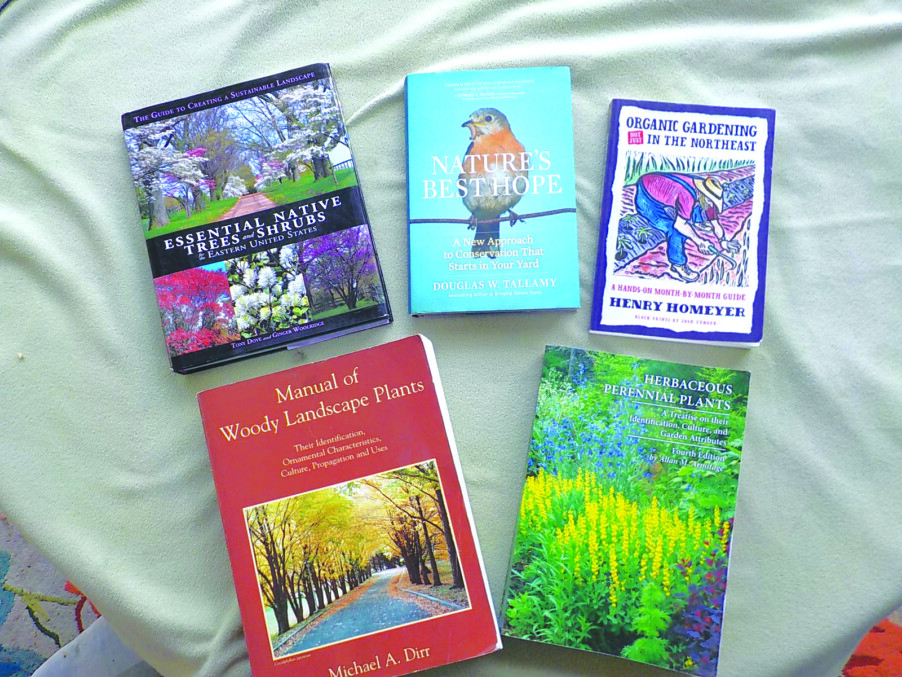

Books are great gifts, and books printed in the United States should be readily available at your local bookstore. My first choice for a book to give? Doug Tallamy’s Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard. It explains how what we plant can affect the planet, especially our pollinators and birds. And all of us, really.

I’ve re-printed my last gardening book and will be selling it at a discount directly to you, signed. It’s a collection of my best articles organized around the calendar year. It’s titled Organic Gardening (not just) in the Northeast: A Hands-On, Month-by-Month Guide. Signed and mailed to you for just $19. Send a check to Henry Homeyer at PO Box 364, Cornish Flat, NH 03746. I will try to figure out how to reduce the price on my website, Gardening-Guy.com where it is currently for sale at $21 if you want to use PayPal.

What else at the bookstore? Essential Native Trees and Shrubs for the Eastern United States by Tony Dove and Ginger Woolridge is a great companion for Doug Tallamy’s book. Michael Dirr has written lots of great tree books. He is informative and opinionated. Allan Armitage is just as opinionated and thorough about flowers as Dirr is about trees. Or get a gift certificate and let your gardener pick her own books at the local bookstore.

If deer are a problem in the garden of your loved one, I find nothing better than Fend Off Deer and Rabbit Repellent Odor Clips, available at Gardener’s Supply and other retailers. A package of 25 sells for about $20. I use one or two per shrub to keep deer away all winter. They clip on with a clothespin-style attachment. They contain just garlic and soy oil, no chemicals.

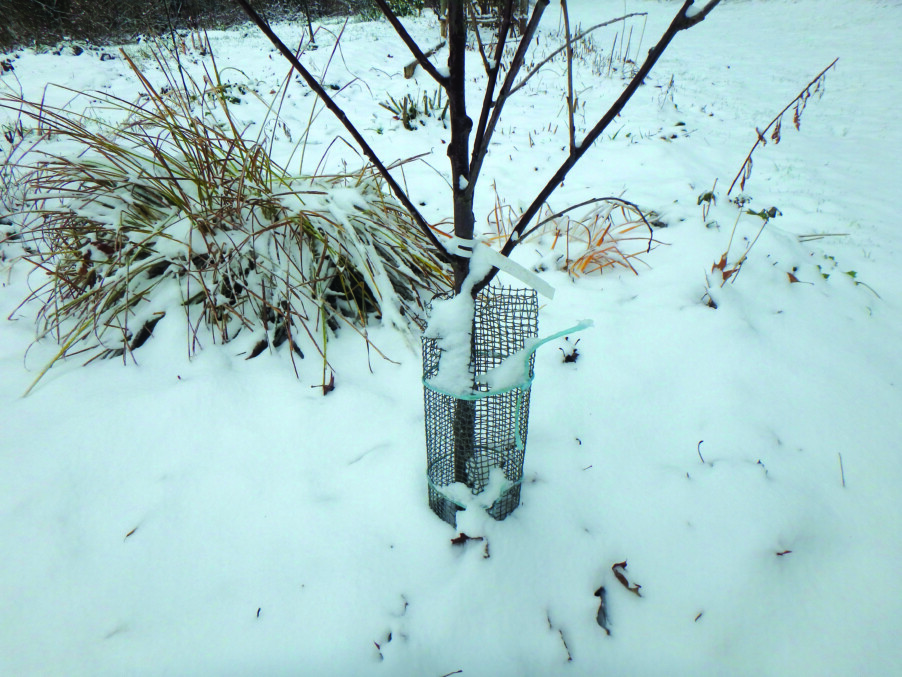

I recently wrote about using hardware cloth (wire screening) to keep voles from chewing off bark and killing young trees. Since then I have used plastic spiral tree guards that are easy to install and will protect against sun scald in winter, too. They are inexpensive and can be reused (I will remove them in the spring). They are sold as Rainbow Professional LTD White Spiral Tree Guards at OESCOinc.com or by calling them at 413-469-4335. They sent my order out the very day I called.

Also available from OESCO are some pruners that I like a lot. OESCO is a small company based in Conway, Massachusetts, catering to orchard professionals. The pruners are made by a German company, Löwe (not to be confused with the American retailer Lowe’s). The pruners are of the anvil type, designed and manufactured well. They sell a size nice for small hands (Löwe 5.107) and a larger size, too. OESCO sells replacement blades and parts.

Of course every gardener needs a good weeding tool. The CobraHead is my favorite and has been for years. They now have a mini-Cobrahead designed for smaller hands. Available from CobraHead.com or 866-962-6272 or at your local garden center. It has a single curved tine like a steel finger that will tease out roots from below while you tug a weed from above. I emailed the owner, Noel Valdes, who told me there are plenty in stock.

I found a wonderful shovel for digging in tough areas with lots of roots. It’s called the Root Slayer and is available from Gardener’s Supply and a few other retailers. I’ve used mine all summer and love it! Great for cutting though sod, too. It has a sharp blade and teeth along the sides for slicing roots.

Lastly, think about a gift certificate at your local nursery or garden center for plant purchases in the spring. Plants are always good.

Featured photo: Gardening books make great presents. Courtesy photo.