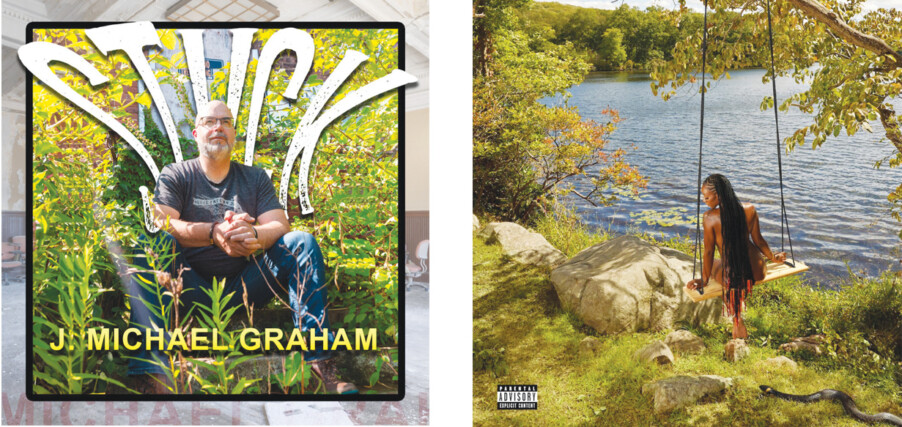

EST Gee, I Ain’t Feeling You (Bonus Edition) (Interscope Records)

This 30-year-old Louisville, Kentucky-born rapper lost a good number of fans after trying actual singing on for size for a couple of albums or so, but his return to straight spitting in this one does go pretty hard, aiming for the same intensity as 2021’s Bigger Than Life or Death. Of course, “intensity” isn’t an attribute that’s usually applied to him, what with his mumbly, disjointed style; he’s been dubbed a “less coherent Rich Homie Quan” among other things, but I was captivated enough by opener “Free Rico” and its woofer-rattling, from-the-mountaintop kettle-drum beat to get past the pedestrian trap undergirding that serves as its base. “The Streets” winds and roils in hypnotic, serpentine fashion, evincing casual excitement and an endless supply of oxygen, instantly lending the record grower potential rather than evoking some texted-in flavor-of-the-week exercise. “Do My Own Stunts” is the underground stoner-a-thon, for those who live for that kind of thing. A —Eric W. Saeger

Friko, Where We’ve Been, Where We Go from Here (ATO Records)

In In-Case-You-Missed-It news, this album didn’t hit my radar until just now, so you have my sincere apologies if you’re already deeply familiar with it. I’m literally a year late on it, but in my defense the angle here is that on Saturday, March 8, they’ll be at The Sinclair in Cambridge, Mass., and besides, at the rate indie bands come and go in the endless flux of our no-attention-span zeitgeist, it’s worth mentioning. This Chicago duo, claiming to be inspired by such acts as Minski and such, are, as some have noted, remindful of Radiohead and Arcade Fire, but there’s a wild-horses feel to these frightwiggy tunes; they incorporate some of the decent things (few though they were) about Aughts-indie bands like New Young Pony Club and Los Campesinos, for one thing the amateurish group-singalong sound that was a staple at Bowery Ballroom shows and later refined by Arcade Fire. The overall effect is like being subjected to a cult initiation; you want to learn the lyrics because the melodies sound so bloody important, a rare thing these days. A —Eric W. Saeger

Playlist

• Happy Valentine’s Day to those who celebrate, and even to those who haven’t dated or even talked to another human being since the 1990s (good choice)! It is another two months before the South Korea-originated “Black Valentine’s Day,” when people who celebrate being “happily single” take themselves out to dinner and a movie and then go home to descend into madness in front of reruns of Classic Concentration on the Buzzr channel, as opposed to us totally happily married people who spend most of our time living like Fred Flintstone, half-watching Match Game ’78 while trying to figure out how to hide ridiculously impulsive Amazon purchases from our spouses, do you guys even know how much money buying a 20-pack of button-cell batteries for kitty laser pointers can save you in the long run? But I digress, someone stop me, the record companies are gearing up for a long year of releasing albums and trying to figure out a way to out-sell Chappell Roan, who won the Best New Artist Grammy award the other week for such things as dressing up like Carol Kane in Scrooged, giving attitude to random people with cameras, and of course her masterstroke, adding gravelly Ed Banger beats to microwaved Madonna oatmeal and summarily dispatching a battalion of record company mafiosi to pressure low-information writers from Nylon and such to proclaim her marginally listenable album The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess to be the greatest thing since Reese’s Cups. This too shall pass, as you know (by the way, are Zola Jesus and Poppy still relevant, someone please tweet at me), but in the meantime we have albums to discuss, new ones that are coming out on Valentine’s Day, let’s get it over with. First things first, speaking of Buzzr, guess who’s got an album coming out on Friday? None other than Richard Dawson! But wait, it’s not that Richard Dawson, the creepy touchy-grabby British dude from Family Feud, it’s a different one, some British folkie whose voice sounds like a drunk Basset hound! Nothing normal is going on here, this man has been using a literally broken guitar as his go-to instrument for years, he just likes the sound of it. His trip has been described as “the folkie version of Captain Beefheart’s approach to blues music.” In other words it’s completely horrible, but our pals at Domino Records are releasing this monstrosity nevertheless, so I’m compelled to listen to it, so I am. OK I’m not anymore, it sounds like the Unabomber singing a love song to his first-grade teacher on a wooden Fisher Price guitar from 1959. If you honestly love this I hate you.

• Usually when I hear the term “space rock” I start barfing uncontrollably, figuring I’m about to hear something that sounds like Spacemen 3 or a Loot Crate version of Pink Floyd, but British band Doves are pretty awesome: They actually sound kind of like Elbow! Constellations For The Lonely, their new one, features the tune “Renegade”; it’s psychedelic, yes, but singer Jimi Goodwin’s voice is seriously neat.

• Oh, great, notoriously awful singer Neil Young has once again found some old tapes in his goat barn and made an album out of them. Oceanside Countryside was recorded in 1977 but never released until now; it features “Field of Opportunity,” a fiddle-driven bluegrass jam that’s OK if you like bad singing with your bluegrass.

• Finally we have Sleepless Empire, the latest LP from Italian goth-metal spazzers Lacuna Coil. The song “Gravity” is doomy and epic, of course, less so when the Cookie Monster-voiced dude is doing the singing, more so when the hot chick singer is trying to sound like an America’s Got Talent contestant. It’s fine for what it is. —Eric W. Saeger

Featured Photo: EST Gee, I Ain’t Feeling You (Bonus Edition) (Interscope Records) & Friko, Where We’ve Been, Where We Go from Here (ATO Records)