Idle Heirs, Life Is Violence (Relapse Records)

Relapse continues to be one of the two or three (tops) metal-focused record labels I actually appreciate getting new stuff from, and the debut LP from this Kansas City crew is yet another spine-crunching assault, if you’ll pardon the metal-centric hyperbole. The “RIYL” (“Recommended If You Like”) list, so they told me, includes Deftones, Mogwai and Cult of Luna (in all honesty I was pleased that anyone knew Cult Of Luna even existed) and that’s right on target. I’d also add Isis as a more-or-less-soundalike, not that this record is as, I don’t know, polite as those guys; what I refer to is the raw intensity. We start with “Loose Tooth,” which lifts off with one of those balladic-acoustic patterns, with Coalesce singer Sean Ingram floating in mellow mode for a bit, and then the thing just explodes as Ingram lets out a Crowbar-worthy yowl that seems to go on forever (it sort of made me chuckle insanely, thinking about the last time a tooth was bothering the heck out of me). Anyway, it’s all overhead-speaker ambiance for Hell, as promised, not for the squeamish. A+

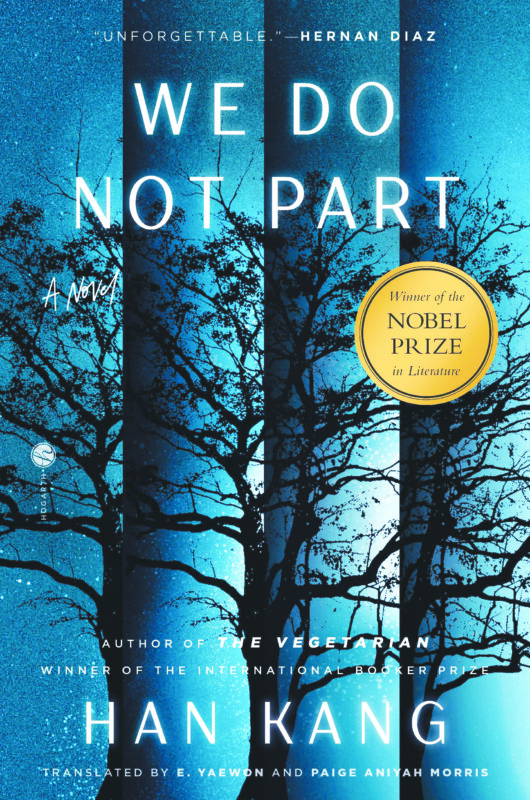

Roi Turbo, Bazooka [EP] (Maison Arts)

Fun act here, comprising two brothers named McCarthy, who grew up in Cape Town, South Africa, with music-loving parents and abandoned their drum lessons for autodidactic strategies (Conor played along to Bloc Party records; Ben learned via YouTube). I liked ’em already just based on that, but what’s even more hilarious and exhilarating is the underlying gay-disco-but-not-quite-gay-disco vibe of “Super Hands” on this five-songer. It’s pretty relentless, really, semi-seriously dabbling with Afrobeat and subsonic Aughts-era house cavitation; it made me think of YouTube’s Hulett Brothers, you know, the guys who do the trick shots with ping-pong balls and whatnot. These are party jams for sure, mildly gritty, slightly Ed Banger-ish instrumentals guaranteed to get heads a-bobbin’, for example “Dystopia,” with its faux-yacht-techno steez, which is punctuated with monkey sounds and ’70s-pop sweetness. They’ll be (very appropriately) supporting Empire Of The Sun at The Music Hall in Boston on May 24. A+

PLAYLIST

A seriously abridged compendium of recent and future CD releases

• And lo, unto the masses the lord (or someone pretending to be Him) commanded from his brunch table, “Let there be new albums dumped unto those peeps on March 28,” and thus it will be, this Friday, because I have no say in the matter! Yes, it’s another new release Friday, as we await “second winter” after a bunch of 60-degree days, but I’m ready for it! Why, you ask? Because I stored a turkey in our freezer in January, back when Market Basket was charging negative ten cents a pound for them or whatnot, so when this year’s Second Winter’s cruel frost sets in, I am going to be eating Second Thanksgiving Dinner, in my house, and then an entire blueberry pie, and then Petunia and I are going to go Christmas caroling in our neighborhood, dressed like Grinches, for the amusement of all the little children! Important note, I saved last year’s Detroit Lions’ Thanksgiving Day game on DVR, so I could watch it on Second Thanksgiving, so please don’t message me to tell me what the final score was, that’d be great, I just want to enjoy Second Winter in style, snoring on the couch! But where were we, oh yes, albums, and look at this, guys, the first thing to hit my radar is none other than Based On A True Story, the first album in 20 years from insane slapping person Will Smith! Wow, so that explains why he keeps coming up in “my socials” and by extension why my Twitter is full of slapping jokes! I was like, “Why is everyone suddenly making fun of the stupidest moment in the history of awards ceremonies, isn’t that old news,” but this explains it: The guy actually thinks we forgot about that incident with Chris Rock, my third favorite comedian after Doug Stanhope and Elon Musk! Well I’ll tell you, I haven’t forgotten, but I suppose there’s always the possibility that his new duet with Big Sean, “Beautiful Scars feat. OBanga,” will be so awesome and underground-hip-hoppy that I’ll be like, “Maybe Chris Rock actually deserved it for all his rotten ‘literally being a funny person’ antics, can’t we just pretend it’s 1990 again?” Nah, it’s awful; as you know, Big Sean peaked with Detroit 2, this is just corporate-hip-hop nonsense, with Auto-Tune, because of course there’s Auto-Tune. Some online person just said something about “Will should do a diss track of Jada Pinkett Smith and have Chris Rock spit some lines.” Ha ha, wouldn’t that be funny, OK, let’s move on from this horror, I’d love that.

• Mumford & Sons, they’re still relevant, aren’t they, or are we already past believing any good music came out in the 2010s? Well, doesn’t matter, the Mumfords’ new album, Rushmere, is getting uploaded to your Spotifys as we speak, and it will include the title track, which is another one of those urgent-sounding galloping-horsie indie-meets-bluegrass tunes those guys specialize in, so yes, it’s cool, if hilariously redundant. You know, they really need to make up their minds about what to do next while they figure out which Vegas theater will give them a residency after their inevitable Grand Ole Opry phase (ack, did that sound cynical, I can never tell).

• Speaking of horsies, there’s pop-metal band The Darkness again, with a new album, called Dreams On Toast, featuring their horsie-voice singer, Whatsisname! The new tune, “I Hate Myself,” sounds like 1970s-era Sweet but super-boring, has anyone ever actually cared about this band, like really seriously, pinkie swear?

• In closing this column, I’d like to say that Deafheaven is still around, as they have a new album coming out momentarily, Lonely People With Power! “Heathen” starts off sounding like Sigur Ros, and then they do their usual black-metal nonsense. I don’t actually hate it, make of that what you will.