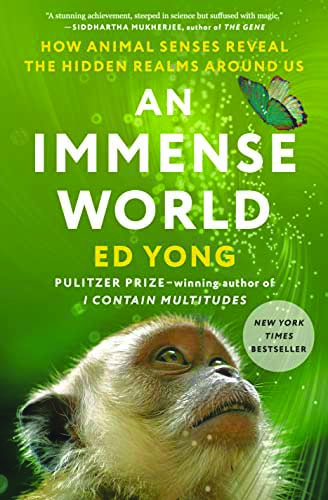

An Immense World, by Ed Yong (Random House, 359 pages)

In the 17th century, the French philosopher and priest Nicolas Malebranche wrote: “animals eat without pleasure, cry without pain, grow without knowing it: they desire nothing, fear nothing, know nothing.”

That hasn’t aged well.

While the sentiment may have been useful for vivisectionists throughout the ages, what’s not self-evidently wrong in the statement has been proven false by research over the past few decades. As for “knowing nothing,” that nonsense is grandly refuted in Pulitzer Prize-winning science writer Ed Yong’s second book, An Immense World.

Animals may not know how to build bridges or perform cardiac surgery, but they possess extraordinary abilities that humans lack, some of which we now well understand (like echolocation), others that we still can’t. Yong walks us through the ongoing research into animals’ capabilities while trying to make sense of their “umwelt” — their “perceptual world.”

“Umwelt” is a German word coined by a biologist in 1909 to describe what it’s like for a spider to be a spider, for a bird to be a bird. It’s impossible to fully understand animals’ perception of their world, but a genre of scientists called sensory biologists are trying. And their research is fascinating, once you push past wondering why tax dollars are going to pay for their experiments. Thankfully, much of this research is going on in other countries.

For example, there is the scientist who studied insects called treehoppers in a Panama forest and listened to the communication of a family by clipping microphones onto a plant and listening with headphones. Without the headphones, he could hear nothing. But headphones allowed him to eavesdrop in the treehopper world, where the insects were making sounds similar to cows mooing. “The sound was deep, resonant, and unlike anything you’d expect from an insect. As the babies settled down and returned to their mother, their cacophony of vibrational moos turned into a synchronized chorus.”

In anecdotes like this, An Immense World seems a sequel to Yong’s first book, 2016’s I Contain Multitudes, in which he explored the microbes that populate the human body. The takeaway from both is that for all our abilities, for all the wonders of the human eye and ear, we are oblivious to much of what is going on around us (and inside us). When we take the time to learn and pay attention, there is as much reason for awe as there is when we contemplate the night sky.

Yong tantalizingly suggests that learning about animals’ seemingly miraculous senses can help us to make better use of our own. Like the oft-quoted aphorism that humans only make use of a fraction of our brain power, it appears that much of our sensory power goes unused.

Yong visits a California man, blinded by cancer in infancy, who naturally learned to echolocate like a bat. He navigates by making a clicking sound and following the echoes. This doesn’t just allow him to walk and bike down streets, but also to do things sighted people can’t do. For example, when Yong accompanies the man on a walk, he asks if someone had parked on their lawn at a house they passed. The car was half on concrete, half on grass. The man was able to perceive this without seeing, just from decades of practicing echolocation. He is blind, but inhabits a rich sensory world that sighted people don’t access; that is his umwelt.

Similarly, animals inhabit worlds that may not be as expansive as ours in some ways, but they are attuned to scents, sensations, chemicals and magnetic and electrical fields we don’t perceive.

As Yong travels the world interviewing scientists who work with animals ranging from manatees to electric fish to rattlesnakes, he explains their extraordinary abilities in largely accessible language (although there are passages in which an advanced degree would help).

He devotes a chapter to the subject that is most controversial in the general population: how animals experience pain. Pain, as Yong describes it, is “the unwanted sense,” and it is a difficult subject for modern scientists to explore, since most of them reject the ancient belief that animals are fundamentally oblivious to it. There is still wide disagreement about to what degree animals experience pain, and whether this is reason enough to stop eating lobster.

What most people call pain is actually two different experiences, Yong explains. The first is nociception, which is our response to painful stimuli, such as touching a hot stove or an electrified fence. Our sense of touch apprehends danger and we pull back instinctively. The pain that follows is a different thing. Some scientists have argued that all animals’ reactions to painful stimuli is nociception, that they can’t suffer as we do. Not everything that is alive has consciousness, which is believed to require a nervous system. And some creatures exhibit behavior in which they do seem oblivious to what we would think of as excruciating pain: say, the male praying mantis that mates with a female that is devouring him.

But research has shown that a wide range of animals subjected to pain will choose painkillers that are offered to them. This is true of even zebrafish. And animals who respond to injury by licking and grooming will stop when given painkillers. But Yong offers no clear answers, like the scientist who tells him, “I’m often asked if crabs and lobsters feel pain, and after 15 years of research, the answer is maybe.”

Yong is more definitive when it comes to what our response should be to new knowledge about how animals’ lives are governed by senses of which we are largely unaware. For example, we now know that the migratory patterns of birds and butterflies are affected by artificial light, that sea turtle hatchlings (which have a 1 in 10,000 shot of enduring to maturity) die because they are drawn to house lights and bonfires when these eclipse the moonlight, which would normally guide them to sea.

The fluttering of moths around a lightbulb can be fatal to them; many die of exhaustion. The “Tribute of Light” that New York City installs each year to commemorate 9/11 can be seen for 60 miles and disrupts the migration of thousands of songbirds, so much so that when too many confused birds start circulating the light, it’s shut off for 20 minutes to allow them to, as your GPS would say, recalculate.

Animals evolve and adapt and many will eventually adjust to modernity if they don’t go extinct. The pandemic showed us, however, that nature can quickly bounce back once humans change their behavior. The first step in doing so is knowledge.

An Immense World is a lackluster title; not so the book. Others have dabbled in this topic, such as primatologist Frans de Waal in 2016’s Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? Yong, who seems incapable of covering a topic superficially, does it better than most. A

Book Events

Author events

• LAURIE STONE presents Streaming Now: Postcards from the Thing That Is Happening at Gibson’s Bookstore (45 S. Main St., Concord, 224-0562, gibsonsbookstore.com) on Thursday, Aug. 4, at 6:30 p.m.

• MARIANNE WILLIAMSON presents The Politics of Love at the Bookery (844 Elm St., Manchester, bookerymht.com, 836-6600) on Wednesday, Aug. 10, at 7 p.m. Free event; register at www.bookerymht.com/our-events.

• KATHLEEN BAILEY and SHEILA BAILEY present their book New Hampshire War Monuments: The Stories Behind the Stones at Gibson’s Bookstore (45 S. Main St., Concord, 224-0562, gibsonsbookstore.com) on Thursday, Aug. 11, at 6:30 p.m.

• R.A. SALVATORE presents Glacier’s Edge at Gibson’s Bookstore (45 S. Main St., Concord, 224-0562, gibsonsbookstore.com) on Friday, Aug. 12, at 6:30 p.m.

• CASEY SHERMAN presents Helltown at the Bookery (844 Elm St., Manchester, bookerymht.com, 836-6600) on Sunday, Aug. 14, at 1:30 p.m. Free event; register at www.bookerymht.com/our-events.

Poetry

• OPEN MIC POETRY hosted by the Poetry Society of NH at Gibson’s Bookstore (45 S. Main St., Concord, 224-0562, gibsonsbookstore.com), starting with a reading by poet Sam DeFlitch, on Wednesday, July 20, from 4:30 to 6 p.m. Newcomers encouraged. Free.

• DOWN CELLAR POETRY SALON Poetry event series presented by the Poetry Society of New Hampshire. Monthly. First Sunday. Visit poetrysocietynh.wordpress.com.

Writers groups

• MERRIMACK VALLEY WRITERS’ GROUP All published and unpublished local writers who are interested in sharing their work with other writers and giving and receiving constructive feedback are invited to join. The group meets regularly Email [email protected].

Book Clubs

• BOOKERY Monthly. Third Thursday, 6 p.m. 844 Elm St., Manchester. Visit bookerymht.com/online-book-club or call 836-6600.

• GIBSON’S BOOKSTORE Online, via Zoom. Monthly. First Monday, 5:30 p.m. Bookstore based in Concord. Visit gibsonsbookstore.com/gibsons-book-club-2020-2021 or call 224-0562.

• TO SHARE BREWING CO. 720 Union St., Manchester. Monthly. Second Thursday, 6 p.m. RSVP required. Visit tosharebrewing.com or call 836-6947.

• GOFFSTOWN PUBLIC LIBRARY 2 High St., Goffstown. Monthly. Third Wednesday, 1:30 p.m. Call 497-2102, email [email protected] or visit goffstownlibrary.com

• BELKNAP MILL Online. Monthly. Last Wednesday, 6 p.m. Based in Laconia. Email [email protected].

• NASHUA PUBLIC LIBRARY Online. Monthly. Second Friday, 3 p.m. Call 589-4611, email [email protected] or visit nashualibrary.org.

Language

• FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE CLASSES

Offered remotely by the Franco-American Centre. Six-week session with classes held Thursdays from 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. $225. Visit facnh.com/education or call 623-1093.