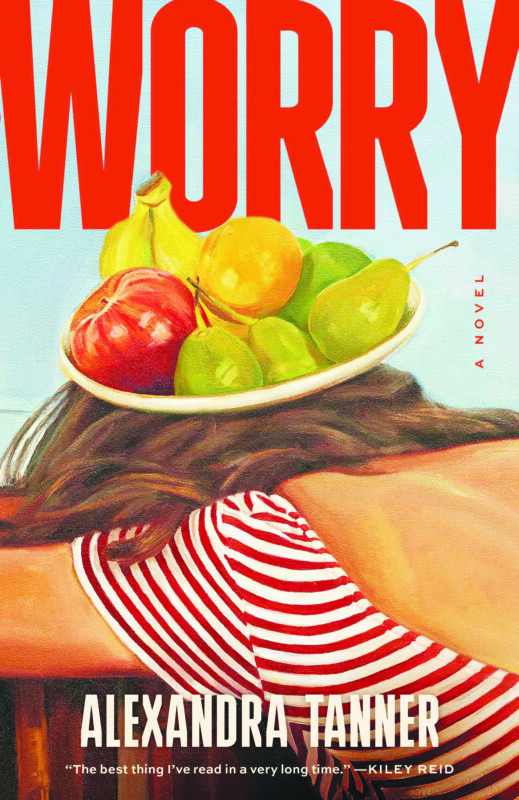

Worry, by Alexandra Tanner (Scribner, 290 pages)

If there’s a twentysomething in your life, or if you are one, you will love Jules and Poppy, the anxious and squabbly sisters in Alexandra’s Tanner’s debut novel, Worry.

And also, at some point, you’ll just want to throttle them.

Tanner has bottled the nervous essence of youthful TikTok and spilled it out on the page in a quirky, pre-Covid novel that is dialogue-driven and plot-deprived but somehow manages to be fun to read.

It begins — and ends — in 2019. Poppy Gold, the younger of the two sisters and ostensibly the least emotionally stable, arrives at Jules’ rent-controlled apartment in Brooklyn, New York.

She takes over her sister’s home office and plans just to stay for a short while until she can find her own place.

Poppy has tried to kill herself and has picked up shoplifting for fun, but she seems to be on the mend emotionally. She, like much of her generation, is highly socially conscious, refusing to let her sister buy a SodaStream because she “doesn’t want to support Israeli apartheid.” She doesn’t have a job but is convinced she can get one and afford the rent on her own place, or else get their parents to subsidize it.

Jules, the narrator, knows better. Jules is somewhat stably employed as an editor for a publishing company that produces study guides similar to SparkNotes, and has a boyfriend with “an MFA in poetry and half a Ph.D. in poetry.”

“He pretends he knows things about wine and I let him. I pretend I know things about Russian literature and he lets me. It’s all very tentative,” Jules says. In her spare time, Jules obsesses over Mormon mommy blogs and picks fights with them in the comments. She calls them her mommies.

Her real mother, and Poppy’s, practices Messianic Judaism, just started an Instagram account (zero followers) and argues with her daughters about whether police are bad or good and is prone to texting them a thumbs-down emoji when they say something she doesn’t like.

“I don’t understand why the three of us can’t ever just have, like, a nice conversation,” Jules says to Poppy, discussing their mother. “Not even a conversation, just a moment even. What’s her deal with us? Why doesn’t she like us?”

“Oh,” Poppy says without looking up, “it’s because she’s a narcissist and we’re her appendages. It says so in the trauma book.”

Soon it becomes clear that Poppy will not be moving out anytime soon, and to the delight of their father, a dermatologist who is always telling his daughters what cosmetic work they need to have done (and does it free), they settle down to housekeeping together. They even adopt a three-legged rescue dog named Amy Klobuchar.

This is the point where there should be some rising story arc, some crisis, some Thelma-and-Louise-esque trip. Astonishingly, there is not. Worry is essentially a book full of snappy dialogue and stream-of-consciousness observations of one millennial and one zoomer. Poppy and Jules are an Algonquin Round Table that seats two.

While they both have dreams — Jules has an MFA and still aspires to be a “real” writer — they are locked in anxiety, self-consciousness and a never-ending loop of videos on the internet that end badly, from 9/11 to a zoo panda’s death. This leads to a conversation about whether watching videos like that changes a person.

Poppy argues yes: “There is a before and after of me watching this video, you know? There’s the me who hadn’t chosen to watch the video, and there’s the me who did. And I’m not the old me anymore.”

To which Jules replies: “The Internet isn’t real, it isn’t experience. It’s moving dots.”

But when Jules ventures out into the real world to watch a writer lecture at a museum, and another young woman tries to befriend her, she refuses to engage and spirals into self-pity. “There’s never been a reality in which I could be a serious thinker, a serious writer. I’m a Floridian. I’m a consumer,” she says to herself.

Tanner disguises the seriousness underlying the women’s unhappiness with her light, comic touch. When, for example, a high-school drama friend reaches out to Jules, Jules admits, “It thrills me to see that she is not working as an actress, that she’s working in nonprofits — the fate of the unremarkable — and that she’s the annoying kind of married where she has her wedding date, bookended with hearts, in her little bio box.”

But Tanner throws the readers under a bus with an emotionally challenging ending that is a sharp and unexpected departure from her modus operandi up to that point. It’s as if she’d been serving cotton candy, and then suddenly left the room and came back with fried alligator. But by that point, it’s too late for the reader to bail.

Worry is, in essence, an anxious monologue that will resonate most with young, under-employed, over-educated Americans who live in large cities on the coasts. B