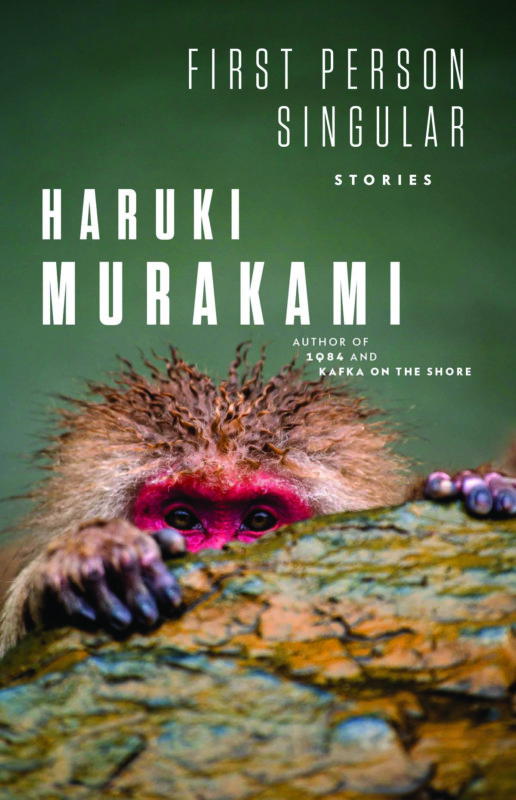

First Person Singular by Haruki Murakami (Knopf, 256 pages)

Type “Haruki Murakami” into the Google search engine, and one of the questions that comes up is “Why is Harukami Murakami so popular?,” which elicits a laugh. Sometimes, wading through his matter-of-fact, beige-to-gray prose, one does have to ask.

Murakami’s characters often seem aimless, their wanderings pointless, and in his longer works, such as 2017’s Killing Commendatore, so can his writing. One scornful critic has called him “the Forrest Gump of global literature.” But it’s not hyperbole to call the Japanese writer a sensation, so for people who would like to sample Murakami without a month-long commitment, there’s an opportunity in First Person Singular, a collection of eight stories that coalesce around love, death, aging and reality.

I think.

Murakami reminds me of the children’s book Nothing Ever Happens on My Block (by Ellen Raskin), in which a glum child sits on a stoop and complains about how boring his life is, while fire trucks zoom by and witches pop up in windows. Surely there’s more going on here than I’m seeing?

But then Murakami has one of his characters, a writer, say to an editor: “Theme? Can’t say there is one,” which seems like a sly confession befitting the owner of a jazz bar who famously decided he would become a novelist one day while watching a baseball game.

I digress, but so does he. That said, after a slow start, First Person Singular is a wonderfully quirky foray into the world of Murakami, the strongest stories being “Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova” and “Confessions of a Shinagawa Monkey.”

In “Charlie Parker,” the narrator begins by recounting a story he wrote in college about the American jazz legend experimenting with bossa nova, a type of music that is an alchemy of jazz and samba. The thing is, Parker died before bossa nova was invented, so the narrator envisions a recording that is fantasy. But one day, browsing through a music store, he comes across a crudely produced recording called “Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova” that lists exactly the same tracks that he had invented. Instead of buying the album ($35 seems a bit much), he leaves the store, but then regrets the decision and returns to the store the next day. What happens next is equally fanciful but compelling, and as with much of Murakami’s work, instructive in music.

“Confessions” is a story that could come from the pen of Stephen King, had King grown up in Japan instead of Maine.

The narrator, yet another trademark Murakami wanderer, checks into a ramshackle inn, where everything is old and decrepit, to include the cat sleeping in the foyer. The inn does have one nice feature, two if you count the vending machine that dispenses beer. (Who knew that such things existed?) It has a glorious hot-springs bath, in which the narrator soaks blissfully for a while. This is where he meets the titular monkey, a grizzled creature that shows up and, in perfect English (actually Japanese, as this, like Murakami’s other work, is a translation), offers to scrub the narrator’s back. Naturally, the narrator wants to learn more, so he invites the monkey to come to his room later for conversation and beer.

There, he learns how the monkey came to learn to speak more eloquently than many human beings and to appreciate opera. He also learned that it’s hard being an educated monkey — one is not accepted by his own kind, nor by the humans that he more closely resembles. And one has a particularly hard time finding love.

So the monkey, over time, developed an oddly touching way of experiencing love without having physical contact with the human women he desired. The method did, however, take something from the women, making it unethical. And when the narrator later meets a woman that he suspects had encountered the monkey, he has his own ethical test, of whether to tell her what had transpired. If, of course, it transpired at all and wasn’t just the fevered imagination of a tired man soaking in a hot spring.

This story was published last year in The New Yorker,as was “With the Beatles,” a rambling recollection of a man remembering his first girlfriend and her older brother, whom he had only met once while he was dating the girl, but then encountered decades later by chance. He had broken up with the girl, who did not “ring my bell,” and both had married someone else, and he was unaware of the shocking turn her life had taken until running into the brother.

The repurposing of previously published stories into a book seems vaguely like cheating, although it is done frequently by authors of stature. So, pro tip: You can find some of these stories by searching the table of contents on Amazon and then searching for them online.

“Carnaval” is built around the composition by Robert Schumann and involves a music-centered relationship with the ugliest woman the narrator has ever known, “the result of a unique force that compressed unattractive elements of all shape and sizes and assembled them together in one place.”

“The Yakult Swallows Poetry Collection,” which appears to be pure memoir (but who knows?), is a man reflecting on his love for baseball, and how he scribbles poetry in a notebook in between action. (“Let’s face it — baseball is a sport done at a leisurely pace.”)

Reading Murakami is also best done at a leisurely pace, lest you feel out of touch with an author who is never in a hurry to get where he is going, and often seems not to know where he is going, which may be the truth. (Theme? What theme?) But it is a singular experience, which is sometimes rewarded with an unexpected jolt of humor, as when Murakami (or his narrator, hard to tell the difference), reflecting on his habits of dressing, says that when looking in his closet of unworn dress shirts, still in the dry-cleaner’s plastic, starts to feel apologetic toward the clothes and tries them on out of kindness. Or when a character flatly intones, “Loving someone is like having a mental illness that’s not covered by health insurance.”

Murakami could be one of the greatest writers of understatement the modern world has known or, equally plausible, an imaginative jazz bar owner who stumbled into literary acclaim. Either way, Murakami fans will thrill to this collection, even though they’ve likely already read much of it. Others will Google “Why is Haruki Murakami so popular?” B-

BOOK NOTES

The demise of physical books was supposed to be e-books; the end of physical bookstores, Amazon. But what if the extinction-level event turned out to be vending machines?

Probably not, but I did do a double take upon learning this week about a nonprofit called Short Edition, which has installed more than 300 “Short Story Dispensers” at locations around the world. Users can choose the length of what they want to read —one minute, three minutes or five — and the machine prints it out, looking scarily like a CVS receipt. (See a demonstration at short-edition.com.)

There don’t appear to be any in New Hampshire, but a map of locations shows a variety of locations, to include airports, universities, wineries and, somewhat disturbingly, libraries. There’s lots to unpack here, including the shrinking American attention span, but this could be an interesting way to expose people to new writers.

Meanwhile, for short reads that don’t come on a receipt, check out:

Spilt Milk by Courtney Zoffness, a two-time resident of Peterborough’s MacDowell Colony, (McSweeney’s, 211 pages) offers essays on motherhood, family connections and Judaism.

Of Color, by Jaswinder Bolina (McSweeney’s, 129 pages), poignant essays on race and identity from a poet who writes that he looks more like the 9/11 hijackers than the firefighters who responded that day.

Love Like That by Emma Duffy-Comparone (Henry Holt and Co., 224 pages). The publisher says these stories are about “brilliant, broken women that are just the right amount of wrong.”

The Glorious American Essay, edited by Phillip Lopate (Pantheon, 928 pages), collects 100 classic essays from colonial America to the present, including luminaries such as E.B. White, Rachel Carson, David Foster Wallace, Lewis Thomas and James Thurber.

Books

Author events

• ERIN BOWMAN Author presents Dustborn. Outside Gibson’s Bookstore (45 S. Main St., Concord). Sat., April 24, 1 to 2:30 p.m. Call 224-0562 or visit gibsonsbookstore.com.

• PADDY DONNELLY Author presents The Vanishing Lake. Presented by The Toadstool Bookshop of Nashua, Peterborough and Keene. Virtual, via Zoom. Sat., April 24, 1 p.m. Call 352-8815 or visit toadbooks.com

• LITERARY COCKTAIL HOUR Presented by Gibson’s Bookstore in Concord. Featuring authors Kat Howard, Kelly Braffet, Cat Valente, and Freya Marskem in conversation with bookstore staff. Virtual, via Zoom. Sat., April 24, 5 p.m. Call 224-0562 or visit gibsonsbookstore.com.

• BILL BUFORD Author presents Dirt: Adventures in Lyon as a Chef in Training, Father, and Sleuth Looking for the Secret of French Cooking. Hosted by The Music Hall in Portsmouth. Virtual. Wed., April 28, 7 p.m. Tickets cost $5. Visit themusichall.org or call 436-2400.

• SUZANNE KOVEN Author presents Letter to a Young Female Physician, in conversation with author Andrew Solomon. Hosted by The Music Hall in Portsmouth. Tues., May 18, 7 p.m. Virtual. Tickets cost $5. Visit themusichall.org or call 436-2400.

Featured photo: First Person Singular